The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim

Because it was grassy and wanted wear,

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I,

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

The road not taken in the very popular Robert Frost poem is not the easier road, or the uphill road, or the less scenic one, or even the road that leads to a less desirable place. The road not taken is one of two roads that look quite the same, which one to pick is not obvious or recommended or even advised. It is a simple fork and the speaker has a choice.

The poem has often been believed to reference the American ideal of individualism, to walk off the beaten path, to take up the challenge and to beat the odds. It is an oft quoted section of many a graduation speech, mostly focused on the last two lines – ‘Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, I took the one less traveled by…’

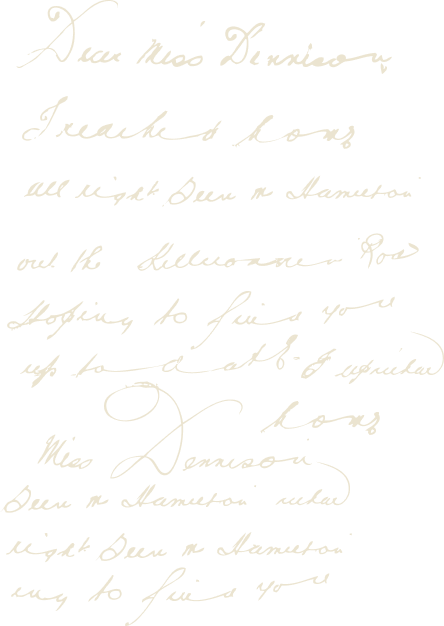

According to David Orr,the poetry columnist for the New York Review of Books and a J.D. from Yale Law School, in his article ‘You’re Probably Misreading Robert Frost’s Most Famous Poem’ (August 16, 2016), Robert Frost first titled the poem Two Roads which he had been inspired to write by his friend Edward Thomas’ habit of constantly wondering where a second path might have led them. The two regularly walked around the countryside of Gloucestershire together. Not only did the two walk together, but they were also best friends, like brothers. Each helped the other with his career, in a way that only poets can.

Frost sent adraft of the poem to Thomas who instead of reading it as a gentle jibe to his ‘crying over what might have been,’ read it the way millions of people have read it since, focusing on the last two lines that imply that the road taken was the less traveled one and that’s what made all the difference in his life. He found it ‘staggering’ and not at all associated with his own dithering. In fact, Thomas, himself a poet and a literary mastermind, thought the poem to be a simple morality tale. But Frost knew that was not possible for how could one assess the outcome of the road not taken. (Mathew Hollis, Edward Thomas, Robert Frost and the Road to War, The Guardian, July 29th 2011).

Frost explained in the ensuing correspondence with his friend that, ‘the operative word in that last stanza was ‘sigh’ and that the sigh was a mock sigh, hypocritical for the fun of the thing.’He chided his friend, ‘no matter which road you take, you’ll always sigh and wish you had taken another.’ (Mathew Hollis)

David Orr says that the poems best known lines, the last two, imply a lonely path that we take at great risk, possibly for great reward. People often assume the poem is called ‘The Road Less Traveled.’ Most google searches for Robert Frost are accompanied by the words Road Less Traveled. But Mathew Hollis writes that Frost himself would warn his audiences – ‘you have to be careful of that one; it’s a tricky poem – very tricky.’

Edward Thomas was troubled with Robert Frost’s explanation of his poem and the jibe about his sigh. But it was not because Thomas had got it so wrong. It was because he felt his friend was making fun of his trouble with making decisions. And he did have trouble with that. He always had. He had suffered from debilitating depression and self-doubt, sought treatment for his ailment and always felt that his American friend was a little too bold, a little too sure and a little too quick with his decision making. This was 1914 and England was at war with Germany. Thomas could not decide whether he should enlist or run off to America as Frost was suggesting. He agonized over the decision. Hollis writes in his article that it was Frost’s poem, The Road Not Taken that pushed Thomas to a decision. He enlisted and shipped out to France. He died in battle only two months after he joined the war.

A young journalist on a Report for America Fellowship to rural Pennsylvania asked if someone is smart and wants to make money, can he/she? The answer is yes. But it depends on how much money. Luck matters a fair amount too. But what matters most is intent, the road taken – if you want to make money, you choose a road that will lead you to jobs that pay well. If you decide that you want to change the world, do good for it and that money matters less, then you take a different road. But both roads are fine – it is a personal choice, a decision.